Speaking of Beethoven

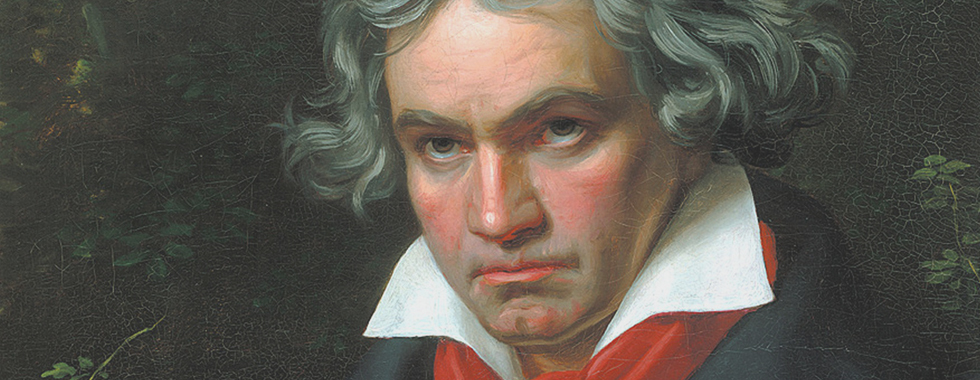

Whenever I think about Ludwig van Beethoven, certain things jump immediately to mind.

Take a minute and think about this great composer; what do you come up with? Probably that he famously went deaf. Maybe that he was a renowned grump. Certainly that he wrote some of the most enduring and sublime music for orchestra, including the 5th and 9th Symphonies (the 5th with its iconic “da-da-da-dum” opening, and the 9th with the infectious and inspiring “Ode to Joy”). I have not-so-fond memories of trying to learn some Beethoven pieces on the piano when I was a teenager and university student. I always wanted to be able to play the beautiful second movement of Beethoven’s Pathètique Sonata, the one whose melody Billy Joel “borrowed” for his song “This Night”. I always felt like I needed another hand if I wanted to be able to play the movement properly, to make the melody sing the right way.

It doesn’t matter what instrument you play, you probably have memories of struggling with Beethoven at some point. He seemed to take joy in writing music that was intensely difficult, too hard for the amateur player. This isn’t surprising, considering that Beethoven was a virtuosic piano player and a perfectionist when it came to composing. So what do we amateurs do when we want to play some Beethoven? Are there compositions that are more accessible than others?

Living as he did at the end of the 18th century and into the beginning of the 19th, Beethoven did not enjoy the same kind of musical employment opportunities as his predecessors.

Bach, for example, spent most of his professional life working as a church composer. Beethoven’s close friend and mentor, Joseph Haydn, worked for the Prince of Esterhàzy for most of his life, enjoying a steady income and consistent employment. Jobs such as these were few and far between at the turn of the 19th century, however, as the authority of the church waned and Europe went through a succession of revolutions against its monarchies (also, Beethoven didn’t like working for anyone but himself!). Thus, Beethoven relied almost entirely on commissions and teaching for his income. He often wrote music for his students, and since he taught students with a variety of skill levels, there are piano works written for a similar range of abilities. Here are some piano pieces for beginner, intermediate, and more advanced students.

The beginner piano player should look to some of Beethoven’s unpublished works.

These were written fairly early in Beethoven’s career (the early 1790s), and thus do not have opus numbers (in other words, they aren’t part of the official Beethoven catalogue of works). Included in these “works without opus number,” or “WoO”, are a couple of Scottish dances called ecossaises. These are charming, short works that are reminiscent of some of Mozart’s earlier piano pieces. Of particular interest are the Ecossaise in E-flat major (WoO 86) and the Ecossaise in G major (WoO 23). These play around RCM Level 1 or 2, so they are not for the absolute beginner, but they are quite accessible to early learners.

There are more pieces available for intermediate piano players.

Beethoven wrote a collection of German Dances (WoO 13) that are interesting and pose some challenge for students playing at the Grade 4 or 5 level. Any of the 12 short works contained in this collection would make for an excellent addition to your recital repertoire. Beethoven also wrote many bagatelles. The word “bagatelle” refers to a “short, unpretentious instrumental composition,” and Beethoven’s bagatelles certainly fit the bill. The sixth bagatelle from his Opus 33 collection would be appropriate for Grade 7 students, as would the Bagatelle in G minor, Op. 119 No. 1. Of course, no discussion of Beethoven’s bagatelles would be complete without mention of perhaps his most played piano work, Für Elise. Historians still aren’t sure exactly who “Elise” was, and this work wasn’t even published during Beethoven’s lifetime (it was discovered over 40 years after his death), but it remains one of his most enduring and endearing works. It is rare to attend a youth piano recital that does not include at least one performance of this bagatelle. It also plays at a Grade 7 level.

The more advanced students may be tempted to take on one of Beethoven’s sonatas, but this can be risky because of the varying ability levels required for different movements of the same sonata.

For example, the first movement of the Moonlight Sonata is appropriate for Grade 7 or 8 students, but the third movement is much more difficult. The same is true of the Pathètique; while the second movement may be accessible to Grade 8 or 9 students, the outer movements require great power and dexterity. A safer approach for students who want to challenge themselves with some of Beethoven’s mid-level advanced works may be to take on a single movement of a sonata, or to consider Sonata No. 19 in G Minor (Op. 49 No. 1) or No. 20 in G Major (Op. 49 No. 2). These are challenging but achievable works for students playing at the Grade 8 or 9 level. They are among the shorter sonatas, having only two movements. More advanced students may want to attempt Sonata No. 25 in G Major (Op. 79). Beethoven also wrote many sets of variations that would provide a good challenge for advanced students. These include Six Variations on a Swiss Folk Song (WoO 64), Six Variations on “Nel cor piu non mi sento,” (WoO 70), and Six Easy Variations on an Original Theme (WoO 77).

Whatever your skill level on the piano, I’m confident that there is a Beethoven composition that is right for you!

Ask your teacher for help tracking down scores for any of these works. Many have appeared in RCM books in the past, while others can be found online for free or in collections of Beethoven’s piano works. Remember, Beethoven wrote almost 100 works for piano, so it’s worth digging into his catalogue beyond stalwarts such as Für Elise and the Moonlight Sonata. Happy playing!

This is an incredible line-up of repertoire! Thank you for sharing these great Beethoven gems, Morgan!